I listened to the news tonight while I ate dinner.

Comment of the day, 9/18/12 (re: saving sex!)

“I believe it is important to reserve sex for marriage, but I also believe it is deeply flawed to put it in terms of ‘Saving it for my future spouse’.

I’m single. I hope there’s a future spouse in the picture–but I don’t know that. I’m not guaranteed that. ‘My future husband’ is a poor motivator, because he may not actually exist. I don’t want to struggle through self-control for decades in pursuit of a fantasy, only to end up burned out and bitter that it was all for nothing.

But if I ‘save sex’, as you put it, because I honor God (and not an imaginary man) with my body, and because I respect what He created sex to be–that’s a different story entirely. That’s a motivation that is sustainable through every season of life. That’s something that can actually lead me into gratitude and awe at the plan of God, rather than resentment for blessings seemingly withheld.

Thanks very much for bringing this perspective to the table.” -Amanda B., as commented today on I am not saving myself for marriage. (I’m saving sex.)

“Arleen Spenceley Writes About Sex.”

It was an honor this week to receive an email from fabulous fellow blogger Edmund Mitchell with an invitation to be interviewed for his blog. I answered questions for him last night. The finished product – a post called “Arleen Spenceley Writes About Sex” – appeared online today. Click here to read it (and to learn the role fried chicken played in my career).

I am not saving myself for marriage. (I’m saving sex.)

I’m not saving myself for marriage.

First, I know no follower of Christ who thinks any of us can save ourselves. Secondly, to say “I’m saving myself” when you mean “I’m saving sex” equates who you are – and therefore your worth – with sex. But your worth is wrapped up in nothing except your existence. It is intrinsic.

So I’m not saving myself.

But I am saving sex.

I should add that the “save” in “saving sex” is not the same as the “save” in “saving the meatloaf for later.” Although I am waiting to have sex, when I say I’m saving sex, I don’t mean I’m “putting it off.” I mean I’m part of an insurrection (albeit it a tiny one) that’s redeeming sex. Refusing, in other words, to treat it like it isn’t sacred.

This isn’t to say sex is not the gift of self. One spouse does give the gift of him or herself to the other, and vice versa, in sex. But I think among the ones of us who have decided to wait until we’re married to have sex, the gift that we give in marriage is misunderstood when we think the gift we are giving is sex.

The gift is the partnership. The constant state of being there. The permanence. The merger of two lives and families into one. I could go on.

Sex is definitely part of it, but it isn’t it.

While saving sex may protect people, physically, emotionally, spiritually, in our hyper-focus on what saving sex does for me, an important truth has been neglected:

Saving sex protects sex.

Sex in our culture, generally speaking, is more about getting than giving. The world says part of it is important (pleasure), and while that part of it is important, I think all parts of it are important. But the world also says parts of it aren’t always necessary (i.e. unity beyond the biological, or fertility). And the world tends to tell us that we who wait are wrong because “everybody’s doing it.”

Because in our culture, “consensus determines rightness or wrongness.”*

But it’s like marriage. “Marriage is a sheet of paper” is parallel to “sex is not sacred.”

Marriage isn’t “just a sheet of paper” because a lot of people suck at it. Marriage is just a sheet of paper when you treat it like it’s just a sheet of paper.

Sex isn’t “not sacred” because 98% of women and 97% of men** don’t reserve it for the context of marriage. Sex is not sacred when you treat it like it’s not sacred.

This is why you could say the people who wait until they are married to have sex, and the people who would get married but never do, and the people who would like to have sex but are celibate because of what they believe about sex, and even the priests and nuns who keep their chastity vows have this in common:

They are all saving sex – redeeming it – by treating it like it’s sacred.

And it is.

– – – –

*From page 26 in Peter Kreeft’s book Back to Virtue.

**According to a National Center for Health Statistics study published in 2011.

Is your love mature or immature?

It took three years and three tries to read (and comprehend) Love and Responsibility, the epic book by John Paul II that made my world a better place.

It took three years and three tries to read (and comprehend) Love and Responsibility, the epic book by John Paul II that made my world a better place.

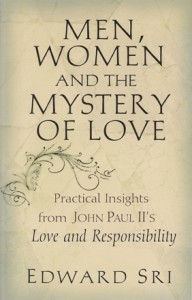

It took fewer than 24 hours to read Men, Women and the Mystery of Love: Practical Insights on John Paul II’s Love and Responsibility by Edward Sri (which, as of tonight, is the twentieth book I’ve read in full in 2012!).

Men, Women and the Mystery of Love makes the same fabulous points Love and Responsibility does, but uses modern language, fewer words, and less paper. It’s Love and Responsibility explained, and its subtitle isn’t kidding: it is totally practical.

While I wholeheartedly implore anyone – Protestant or Catholic, denominational or non, male or female, in church or out – who is now or might someday be a spouse to read Love and Responsibility, Sri’s explanation of it is a close second, an easier-to-read (and quicker!) alternative to hold you over until you can read the real thing. But for now, read on for some of my favorite insights:

On friendship:

“According to Aristotle, there are three kinds of friendship based on three kinds of affection that unite people. First, in a friendship of utility, the affection is based on the benefit or use the friends derive from the relationship. … Second, in a pleasant friendship the basis of affection is the pleasure one gets out of the relationship. One sees the friend as a cause of some pleasure for himself. This friendship is primarily about having fun together. … Aristotle notes that while useful and pleasant friendships are basic forms of friendship, they do not represent friendship in the fullest sense. Useful and pleasant friendships are the most fragile. They are the least likely to stand the test of time because when the mutual benefits or fun times no longer exist, there is nothing left to unite the two people.” -pages 12-13

“For Aristotle, the third form of friendship is friendship in the fullest sense. It can be called virtuous friendship because the two friends are united not in self-interest but in the pursuit of a common goal: the good life, moral life that is found in virtue. The problem with useful and pleasant friendships is that the emphasis is on what I get out of the relationship. However, in the virtuous friendship the two friends are committed to pursuing something outside themselves, something that goes beyond each of their own self interests. And it is this higher good that united them in friendship.” -pages 14-15

“With this background in mind, John Paul II gives us the key that will prevent our relationships from falling into the self-centered waters of utilitarianism. He says the only way two human persons can avoid using each other is to relate in pursuit of a common good, as in the virtuous friendship.” -page 15

On friendship in marriage:

“Pope John Paul II reminds us that true friendship, especially friendship in marriage, must be centered on the bond of a common aim. In Christian marriage, that common aim involves the union of the spouses, the spouses serving each other and helping each other grow in holiness, and the procreation and education of children.” -page 16

“John Paul II explains that being united in this common good helps spouses ensure that one person is not being used or neglected by the other. ‘When two different people consciously choose a common aim this puts them on a footing of equality, and precludes the possibility that one of them might be subordinated to the other’ (28-29). This is so because both are equally ‘…subordinated to that good which constitutes their common end’ (28-29).” -pages 16-17

On the sexual urge:

“…the sexual urge is not an attraction to the physical or psychological qualities of the opposite sex in the abstract. John Paul II emphasizes that these attributes only exist in a concrete human person. For example, no man is attracted to blonde or brunette in the abstract. He is attracted to a woman – a particular person – who may have blonde or brunette hair.” -page 23

“The reason John Paul II emphasizes this point is that he wants to show how the sexual urge ultimately is directed toward a human person. Therefore, the sexual urge is not bad in itself. In fact, since it is meant to orient us toward another person, the sexual urge can provide a framework for authentic love to develop.” -page 24

On sensuality:

When “a man is attracted physically to the body of a woman, and a woman is attracted to the body of a man, (the pope) calls this attraction to the body sensuality.” -page 32

“…an initial sensual reaction is meant to orient us toward personal communion, not just bodily union. It can serve as an ingredient of authentic love if it is integrated with the higher, nobler aspects of love such as good will, friendship, virtue or self-giving commitment.” -page 33

“Especially in a highly sexualized culture like ours, we are constantly bombarded with sexual images exploiting our sensuality, getting us to focus on the bodies of members of the opposite sex.” -page 37

On freedom:

“…freedom is given for a purpose, for the sake of love. God gave us freedom so that we could choose to live for others, not just ourselves. The purpose of freedom is not to equip us to live a selfish life, slavishly pursuing whatever pleasurable desires come our way. We have freedom so that we can choose to rise above those self seeking passions and commit ourselves to other persons, serving them and their needs.” -page 64

“Matthew Kelly writes in his book The Seven Levels of Intimacy: ‘But in order to love, you must be free, for to love is to give your self to someone or something freely, completely, unconditionally, and without reservation. It is as if you could take the essence of your very self in your hands and give it to another person. Yet to give your self – to another person, to an endeavor, or to God – you must first possess your self. This possession of self is freedom. It is a prerequisite for love, and is attained only through discipline. This is why so very few relationships thrive in our time. The very nature of love requires self-possession. Without self-mastery, self-control, self-dominion, we are incapable of love… The problem is we don’t want discipline. We want someone to tell us that we can be happy without discipline. But we can’t. … The two are directly related.” -page 66

On immature love versus mature love:

“When love is immature, the person is constantly looking inward, absorbed in his own feelings. Here, the subjective aspect of love reigns supreme. He measures his love by the sensual and emotional reactions he experiences in the relationship.” -page 79

“A mature love, however, is one that looks outward. First, it looks outward in the sense that it is based not on my feelings, but on the honest truth of the other person and on my commitment to the other person in self giving love. The emotions still play an important part, but they are grounded in the truth of the other person as he or she really is (not my idealization of that person). … Second, a mature love looks outward in the sense that the person actively seeks what is best for the beloved. The person with a mature love is not focused primarily on what feelings and desires may be stirring inside him. Rather, he is focused on his responsibility to care for his beloved’s good. He actively seeks what is good for her, not just his own pleasure, enjoyment and selfish pursuits.” -pages 79-80

– – – –

Click here to learn more about Men, Women and the Mystery of Love.

Disclosure: This post contains affiliate links. So, if you click the links and purchase the products I recommend, I earn a little commission at no extra cost to you. And when you do, I am sincerely grateful.