According to Yale Law professor Amy Chua, Chinese mothers are superior to western ones.

“A lot of people wonder how Chinese parents raise such stereotypically successful kids,” she said in an essay that appeared in Saturday’s Wall Street Journal. “They wonder what these parents do to produce so many math whizzes and music prodigies, what it’s like inside the family, and whether they could do it too. Well, I can tell them, because I’ve done it. Here are some things my daughters, Sophia and Louisa, were never allowed to do:

• attend a sleepover

• have a playdate

• be in a school play

• complain about not being in a school play

• watch TV or play computer games

• choose their own extracurricular activities

• get any grade less than an A

• not be the No. 1 student in every subject except gym and drama

• play any instrument other than the piano or violin

• not play the piano or violin.”

In the essay, an excerpt from her new book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, Chua uses the phrase “Chinese mothers” loosely. She’d say the way of a “strict” western parent pales in comparison to the strictness of authoritarian Chinese mothers who, for the record, aren’t necessarily from China. In the west, she said, parents are obsessed with self esteem. They assume their children are fragile. Chinese mothers, she said, assume their children are strong. In effort to assure that her children are the best and that they grow up to be people like Yale Law professors, a Chinese mother demands perfection via “rote repition,” hours of practicing musical instruments and hours of practice academic tests. Additionally, Chua says that in the process, Chinese parents can get away with what western ones can’t. A Chinese mother, for instance, can call her kid a fatty if he or she is overweight. She can call her daughter garbage if the kid disrespects her at a dinner party and she can revoke her daughter’s right to get up from the piano bench to go to the bathroom until the song she’s practicing is perfect (true stories!).

Some of the things Chua said make me cringe. And some of the things that make me cringe also make sense (which is alarming).

I’m neither Chinese, nor a mother, but I can say with certainty that I wouldn’t call a kid garbage or fatty. I wouldn’t withhold a kid’s right to go to the bathroom. But for her kids, it works. It also worked for Chua, and without any lasting emotional scars or mental illnesses (so she says).

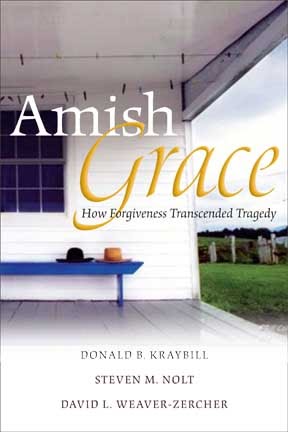

Last night, I finished reading the book Amish Grace (this will be relevant shortly). It’s about the shooting at that Amish schoolhouse in Pennsylvania in 2006. Hours after the shooting, people from the Amish community visted the wife and parents of the shooter (who killed himself after he shot 10 Amish girls, half of whom died). They expressed forgiveness for what the shooter had done and offered sympathy for his family’s loss. Later that week, several Amish people went to the shooter’s funeral, including some of the parents of girls who died. The media bombarded the public with the story of grace and for the most part, it moved people all over the country. When approached by the media, the Amish people were taken aback that the non-Amish were taken aback by something so average in Amish culture. Forgiveness is a given. There is no grudge. The writers of the book, who are experts in Amish culture, delved more deeply into what happened, and they warn: “…the fact that forgiveness is so deeply woven into the fabric of Amish life should alert us that their example, inspiring as it is, is not easily transferable to other people in other situations. Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, but how does one imitate a habit that’s embedded in a way of life anchored in a five-hundred-year history?”

There is a lot embedded in Amish life, like no TV and no driving and no mall shopping trips. These are rules, for lack of a better term, that if imposed upon non-Amish American kids would provoke an unending series of temper tantrums. But an Amish kid would never respond that way.

I think the “Chinese motherhood” Chua writes about is embedded in that culture in the same way forgiveness and no TV are embedded in Amish culture. As a result, if you live in that culture, or if that culture is lived in your house and family, an Amish kid doesn’t have a tantrum because he or she can’t watch TV. You may not be emotionally scarred if your mom calls you garbage in Chua’s culture (although I’d like to see some studies on the mental health of adults who grew up with “Chinese mothers”). But even though thanks to the culture in which I grew up part of me wants to fight Chua on behalf of her kids, I’m compelled to partly defend her because westerners really are obsessed with self esteem, and to a fault.

My favorite quote from Chua’s essay is as follows:

“What Chinese parents understand is that nothing is fun until you’re good at it. To get good at anything you have to work, and children on their own never want to work, which is why it is crucial to override their preferences.”

When you live in a culture where everybody gets a trophy, including the kids on a losing team, you learn to expect rewards regardless of how good you are at what you do. You learn not to work harder (it’s still fun when you aren’t good at something but you get a trophy for it anyway). You believe you must enjoy everything you do, including all the things you have to do between high school and meeting goals like getting your dream job. And then you become an adult who doesn’t want to do anything.

The western assumption of fragility over strength is probably what causes western kids to be so fragile. In fact, in the human growth and development class I took a year ago, I learned that if you shield infants and kids from stressful experiences, the part of the brain that buffers stress won’t fully develop and the kid won’t have the ability to cope with stress for the rest of his or her life.

But is causing stress in the life of your kid the right way to prevent that? I have a hunch that it isn’t.

I also have a hunch that there are plenty of Yale Law professors who didn’t grow up with “Chinese mothers.”

To read Chua’s story in full, click here. (And thanks to Alex for bringing it to my attention!)