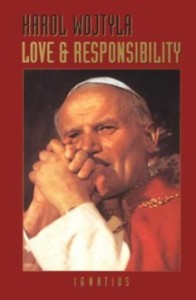

If I tried, I couldn’t concoct a sufficient synopsis nor come up with enough pomp to express with exactness how completely Love and Responsibility blew my mind. The book – the fifteenth I’ve read in full in 2012 – is by Karol Wojtyla, who is both brilliant and Pope John Paul II before he was pope.

The book is about love, marriage and sex and is chock full of profundity and articulate versions of the reasons you give when your friends ask why you’re so excited not to have sex until you’re married. (That happens to everybody, right?)

To anybody who has hopes or plans to wed, I offer a suggestion: PLEASE DON’T BOOK THE CHURCH UNTIL YOU’VE READ THIS BOOK. Worst case scenario? You’ll call off the wedding. But best case, you will learn how to exemplify with your marriage what marriages in our culture rarely really involve: Love.

See below for commentary and several of my favorite excerpts.

On sex, and on what love isn’t:

Wojtyla, to whom I’ll refer as JP2 for the rest of this post (because it’s way easier to spell), writes a lot at the beginning of the book on utilitarianism (the idea that the value of a thing is in how useful it is to you, the philosophy that aims for the greatest good for the greatest number of people), and egoism (which, simply put, is self-focus).

JP2’s description of egoism reminds me a lot of the reasons lots of people give for why it’s important to have sex with a person before you marry him or her:

- “If sexual satisfaction and compatibility aren’t at least quick to achieve if not effortless, the sex is bad…and I don’t want to commit to a life of bad sex.”

- “What if I marry a person who doesn’t know what he or she is doing in sex?”

- “What if his penis is small?”

…all of which boil down to “I always have to have what I want,” a.k.a. egoism, or, frankly, selfishness.

I encountered a guy once who said while he won’t wait until marriage to have sex, it isn’t because he’s selfish. He isn’t selfish, he said. In fact, he added, he is generous in the bedroom – eager to pleasure whatever woman winds up there. He enjoys pleasing her (whoever she is).

To which JP2 would probably say this:

“If, while regarding pleasure as the only good, I also try to obtain the maximum pleasure for someone else – and not just for myself, which would be blatant egoism – then I put a value on the pleasure of this other person only in so far as it gives pleasure to me: it gives me pleasure, that someone else is experiencing pleasure. If, however, I cease to experience pleasure, or it does not tally with my ‘calculus of happiness’ – (a term often used by utilitarians) then the pleasure of the other person ceases to be my obligation, a good for me, and may even become something positively bad. I shall then – true to the principles of utilitarianism – seek to eliminate the other person’s pleasure because no pleasure for me is any longer bound up with it – or at any rate the other person’s pleasure will become a matter of indifference to me, and I shall not concern myself with it. It is crystal clear that if utilitarian principles are followed, a subjective understanding of the good (equating the good with the pleasurable) leads directly, through there may be no conscious intention of this, to egoism.” -page 38

And egoism and love, JP2 says, are incompatible.

“…an objective common good is the foundation of love, and individual persons, who jointly choose a common good, in doing so subject themselves to it. Thanks to it they are united by a true, objective bond of love which enables them to liberate themselves from subjectivism and from the egoism which it inevitably conceals. Love is the unification of persons.

In reply to this reproach consistent utilitarians can (must, indeed) invoke something called the harmonization of egoisms, and a dubious idea it is too, since, as we have seen, on utilitarian premises, there is no escape from egoism. Is it possible to harmonize different egoisms? Is it possible, for instance, to achieve harmony, in the sexual context, between the egoism of a man and that of a woman? This certainly can be done according to the principle ‘greatest possible pleasure for each of the two persons’ – but the practical application of this principle can never deliver us from egoism. Egoism will remain egoism in this type of harmony, the only difference being that these two egoisms, the man’s and the woman’s, will match each other and be mutually advantageous. The moment they cease to match each and to be of advantage to each other, nothing at all is left of the harmony. Love will be no more, in either of the persons or between them … ‘Love’ in this utilitarian conception is a union of egoisms, which can hold together only on condition that they confront each other with nothing unpleasant, nothing to conflict with their mutual pleasure. Therefore love so understood is self-evidently merely a pretence which has to be carefully cultivated to keep the underlying reality hidden: the reality of egoism, and the greediest kind of egoism at that, exploiting another person to obtain for itself its own ‘maximum pleasure.’ In such circumstances, the other person is and remains only a means to an end, as Kant rightly observed in his critique of utilitarianism.” p. 38-39

To use someone as a means to an end is a violation of what JP2 calls “the personalistic norm.”

“This norm, in its negative aspect, states that the person is the kind of good which does not admit of use and cannot be treated as an object of use and as such the means to an end. In its positive from the personalistic norm confirms this: the person is a good towards which the only proper and adequate attitude is love. This positive content of the personalistic norm is precisely what the commandment to love teaches.” -p. 41

Something else often mistaken for love, he writes, is something that is, in truth, only part of love: sentimentality.

“Feelings arise spontaneously – the attraction which one person feels towards another often begins suddenly and unexpectedly – but this reaction is in effect ‘blind.’ Where the feelings are functioning naturally, they are not concerned with the truth about their object. … And this is just where emotional-affective reactions often tend to distort or falsify attractions: through their prism, values which are not really present at all may be discerned in a person. This can be very dangerous to love. For when emotional reactions are spent – and they are naturally fleeting – the subject, whose whole attitude was based on such reaction, and not on the truth about the other person, is left as it were in a void, bereft of that good which he or she appeared to have found. … This is why in any attraction – and indeed, here above all – the question of the truth about the person towards whom it is felt is so important.” -p. 77-78

On what love is:

“Love in the full sense of the word is a virtue, not just an emotion, and still less a mere excitement of the senses. This virtue is produced in the will and has at its disposal the resources of the will’s spiritual potential: in other words, it is an authentic commitment of the free will of one person, resulting from the truth about another person.” -p. 123

JP2 also writes that love is selfless, but that because it’s selfless does not mean a man or a woman will be stifled, or that either spouse should sacrifice any part of who he or she truly is. In fact, the opposite is true:

“Love proceeds by way of this renunciation (of ‘autonomy’), guided by the profound conviction that it does not diminish and impoverish, but quite the contrary, enlarges and enriches the existence of the person. What might be called the law of ekstasis seems to operate here: the lover ‘goes outside’ the self to find a fuller existence in another.” -p. 125-126

And love, not sex, leads to unity. Sex comes later:

“From the ethical point of view the important thing here is not to invert the natural order of events, and not to deny any one of them its place in the sequence. The unification of the two persons must first be achieved by way of love, and sexual relations between them can only be the expression of a unification already complete.” -page 127

On why it’s important to commit “as a result of the truth about a person” instead of solely your senses or your sentiments:

“(Love) is put to the test most severely when the sensual and emotional reactions themselves grow weaker, and sexual values as such lose their effect. Nothing then remains except the value of the person, and the inner truth about the love of those concerned comes to light. If their love is a true gift of self, so that they belong to each other, it will not only survive but grow stronger and sink deeper roots. Whereas if it was never more than a sort of synchronization of sensual and emotional experiences, it will lose its raison d’etre and the persons involved in it will suddenly find themselves in a vacuum. We must never forget that only when love between human beings is put to the test can its true value be seen.” -p. 134

On chastity (and how our culture feels about it):

“Has the virtue of chastity in particular ceased to be respectable? … in modern man, (there is a) characteristic spiritual attitude which is inimical to sincere respect for it: (Resentment.)

Resentment arises from an erroneous and distorted sense of values. It is a lack of objectivity in judgement and evaluation, and it has its origin in weakness of will. The fact is that attaining or realizing a higher value demands a greater effort of will. So in order to spare ourselves the effort, to excuse our failure to obtain this value, we minimize its significance, deny it the respect which it deserves, even see it as in some way evil, although objectivity requires us to recognize that it is good. Resentment possesses as you see the distinctive characteristics of the cardinal sin called sloth. St. Thomas defines sloth as ‘a sadness arising from the fact that the good is difficult.’ This sadness, far from denying the good, indirectly helps to keep respect for it alive in the soul. Resentment, however, does not stop at this: it not only distorts the features of the good but devalues that which rightly deserves respect, so that man need not struggle to raise himself to the level of the true good, but can ‘light-heartedly’ recognize as good only what suits him, what is convenient and comfortable for him. Resentment is a feature of the subjective mentality: pleasure takes the place of superior values.” -p. 143-144

On marriage:

Some people who aren’t proponents of saving sex for marriage wonder why we wait until marriage – why informal commitment isn’t enough. JP2 answers that question, and adds the reason why Catholics (tend to) opt for church weddings (on top of legal ones):

Believers who intend to marry “must seek justification above all in (God’s) eyes, must obtain His approval. It is not enough for a woman and a man to give themselves to each other in marriage. If each of these persons is simultaneously the property of the Creator, He also must give the man to the woman, and the woman to the man, or at any rate approve the reciprocal gift of self implicit in the institution of marriage.” -p. 214

In other words, a church wedding is a ceremony in which as a man and a woman receive each other from each other, they also receive each other from God, to whom they both belong.

Which is beautiful.

– – – – –

Click here to learn more about Love and Responsibility.