|

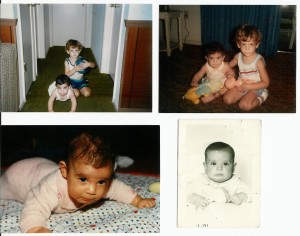

| The babies are me, except for bottom right. That’s my mom, and – obvs – I am her clone. |

Why parents are important.

I write tonight with tight lungs and tired eyes.

“Who we are and how we engage with the world are much stronger predictors of how our children will do than what we know about parenting.

If we want to teach our chilldren to dare greatly in this ‘never enough’ culture, the question isn’t so much ‘Are you parenting the right way?’ as it is: ‘Are you the adult that you want your child to grow up to be?’ -Brene Brown, from her book Daring Greatly

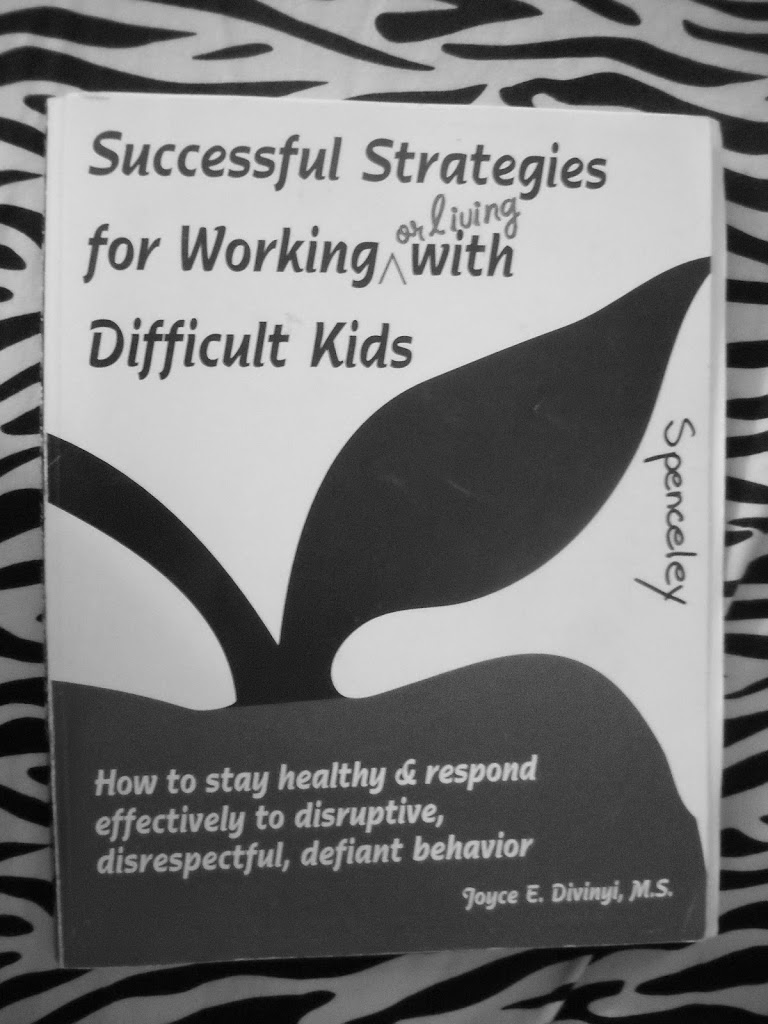

Books in 2012: Successful Strategies for Working (or Living) with Difficult Kids

In prep for my second counseling practicum (which starts Aug. 27 – prayers are appreciated!), in which I’ll work with children and adolescents, I borrowed a bunch of relevant books from my mom, who is a therapist.

One of them – Successful Strategies for Working or Living with Difficult Kids by Joyce E. Divinyi – is the 18th book I’ve read in full in 2012.

What I ultimately got out of the book is a better understanding of the importance of rising above your reflexes. When a difficult child is agitated, it might be instinctual to yell back, or return insult for insult, or criticize the kid for bad behavior. But those responses (and others like them) meet the needs of the adult (to be right, to be liked, to protect the ego, for instance). This is a problem because while the adult is meeting a need of his or her own, a child’s need goes unmet – the need for a role model, for example, or the need to be encouraged, even as he or she appears prepared to make a bad decision, to make a good choice (and that you believe he or she can do that).

The book is chock full of gems, as helpful for parents and future parents as for people whose professions require work with difficult kids (defined in the book as either defiant/disruptive or lethargic/unmotivated, whose emotional development might be arrested, all for a variety of reasons, including but not limited to having experienced a childhood trauma).

Here are some of my favorite excerpts:

On judging children:

“Just as our emotional reactions to these children lead to judgments, our judgments have a significant impact on our expectations for these children. And children respond to our expectations. If we believe they are trouble, and will continue to be trouble, often they are. … The first step, therefore … is to suspend your judgments. … Start with the idea that this child has the potential for success at some level, and that with creativity, perseverance and the right structure, you just may be the one to help him or her succeed.” -pages 22-23

On the problem with “passive activity”:

“Passive activity may sound like a contradiction in terms but it is a good way to describe television viewing. Many children are being overexposed to passive activity because they spend most of their free time in front of a television. It is not just the content of television programming that can have an impact on their lives. … (There are) some excellent programs available for children and adolescents–but there are many things children can never experience or learn by passively watching. … how to play, how to imagine, how to problem solve, how to communicate, how to handle their emotions, how to think, how to develop a skill, how to overcome mistakes, how to set goals, how to compete, how to work, how to interact with others, how to respond to authority, how to discern right from wrong.” -pages 30-31

On discerning the difference between appropriate and inappropriate behavior:

“If the behavior is unacceptable in the workplace, make it unacceptable in the classroom. … If a behavior would get someone fired in the workplace, it should not be tolerated in the classroom.” -page 49

On predicting a positive future:

“Be careful not to predict a negative future. Do not say, ‘If you keep this up, you are going to fail.’ Say instead, ‘You’re too smart to fail. If you decide to work hard at this, you will pass.'” -page 56

“It is especially helpful to affirm their ability to make a good choice when they are very agitated and most apt to do something wrong. You can say, ‘You’re a smart person. You can make a good choice now,’ in the place of saying, ‘You better not do that!’ or ‘If you do that, I’ll…'” -page 57

On giving kids choices instead of demands:

“(Say) … “These are choices, these are the consequences and these are the benefits or rewards,”. The system helps eliminate angry reactions and battles of the will by defining expectations in the form of choices the child makes rather than demands you make.” -page 65

On the importance of being consistent:

“Inconsistency in your responses to inappropriate behavior reinforces the very behavior you are trying to eliminate.” -page 73

On the importance of being firm, but respectful (i.e. don’t yell or talk down, don’t use “threatening words, tones or gestures”):

“These children need instruction in appropriate behavior and they need role models for positive behavior, conflict resolution and anger management. You are the model. You must show them how people work out differences or deal with angry feelings without being destructive to themselves or others. Many times you are their only opportunity to see these skills and traits in action.” -page 75

Yelling “communicates the message that you are not in control of yourself.” -page 84

On praising the deed instead of the person:

“Praise should always focus on behavior or actions, not on personality or personhood. Say, ‘You did great.’ Do not say, ‘You are a great guy.’ Say, ‘It was so good to hear you use words to express your anger instead of hitting or yelling.’ Do not say, ‘You are so good because you are learning to say your feelings.'” -page 88

On our mission with children:

“Sometimes parents, and even those of us who work with children, forget that our mission is to teach children to be independent of us.” -page 95

On why kids should experience reasonable, natural consequences:

“…When you take away opportunities to experience the consequences of mistakes, you rob children of their personal power, especially the power of resilience.” -page 97

– – – – –

Click here to read about all the books I read in 2012.

“Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior”

According to Yale Law professor Amy Chua, Chinese mothers are superior to western ones.

“A lot of people wonder how Chinese parents raise such stereotypically successful kids,” she said in an essay that appeared in Saturday’s Wall Street Journal. “They wonder what these parents do to produce so many math whizzes and music prodigies, what it’s like inside the family, and whether they could do it too. Well, I can tell them, because I’ve done it. Here are some things my daughters, Sophia and Louisa, were never allowed to do:

• attend a sleepover

• have a playdate

• be in a school play

• complain about not being in a school play

• watch TV or play computer games

• choose their own extracurricular activities

• get any grade less than an A

• not be the No. 1 student in every subject except gym and drama

• play any instrument other than the piano or violin

• not play the piano or violin.”

In the essay, an excerpt from her new book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, Chua uses the phrase “Chinese mothers” loosely. She’d say the way of a “strict” western parent pales in comparison to the strictness of authoritarian Chinese mothers who, for the record, aren’t necessarily from China. In the west, she said, parents are obsessed with self esteem. They assume their children are fragile. Chinese mothers, she said, assume their children are strong. In effort to assure that her children are the best and that they grow up to be people like Yale Law professors, a Chinese mother demands perfection via “rote repition,” hours of practicing musical instruments and hours of practice academic tests. Additionally, Chua says that in the process, Chinese parents can get away with what western ones can’t. A Chinese mother, for instance, can call her kid a fatty if he or she is overweight. She can call her daughter garbage if the kid disrespects her at a dinner party and she can revoke her daughter’s right to get up from the piano bench to go to the bathroom until the song she’s practicing is perfect (true stories!).

Some of the things Chua said make me cringe. And some of the things that make me cringe also make sense (which is alarming).

I’m neither Chinese, nor a mother, but I can say with certainty that I wouldn’t call a kid garbage or fatty. I wouldn’t withhold a kid’s right to go to the bathroom. But for her kids, it works. It also worked for Chua, and without any lasting emotional scars or mental illnesses (so she says).

Last night, I finished reading the book Amish Grace (this will be relevant shortly). It’s about the shooting at that Amish schoolhouse in Pennsylvania in 2006. Hours after the shooting, people from the Amish community visted the wife and parents of the shooter (who killed himself after he shot 10 Amish girls, half of whom died). They expressed forgiveness for what the shooter had done and offered sympathy for his family’s loss. Later that week, several Amish people went to the shooter’s funeral, including some of the parents of girls who died. The media bombarded the public with the story of grace and for the most part, it moved people all over the country. When approached by the media, the Amish people were taken aback that the non-Amish were taken aback by something so average in Amish culture. Forgiveness is a given. There is no grudge. The writers of the book, who are experts in Amish culture, delved more deeply into what happened, and they warn: “…the fact that forgiveness is so deeply woven into the fabric of Amish life should alert us that their example, inspiring as it is, is not easily transferable to other people in other situations. Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, but how does one imitate a habit that’s embedded in a way of life anchored in a five-hundred-year history?”

There is a lot embedded in Amish life, like no TV and no driving and no mall shopping trips. These are rules, for lack of a better term, that if imposed upon non-Amish American kids would provoke an unending series of temper tantrums. But an Amish kid would never respond that way.

I think the “Chinese motherhood” Chua writes about is embedded in that culture in the same way forgiveness and no TV are embedded in Amish culture. As a result, if you live in that culture, or if that culture is lived in your house and family, an Amish kid doesn’t have a tantrum because he or she can’t watch TV. You may not be emotionally scarred if your mom calls you garbage in Chua’s culture (although I’d like to see some studies on the mental health of adults who grew up with “Chinese mothers”). But even though thanks to the culture in which I grew up part of me wants to fight Chua on behalf of her kids, I’m compelled to partly defend her because westerners really are obsessed with self esteem, and to a fault.

My favorite quote from Chua’s essay is as follows:

“What Chinese parents understand is that nothing is fun until you’re good at it. To get good at anything you have to work, and children on their own never want to work, which is why it is crucial to override their preferences.”

When you live in a culture where everybody gets a trophy, including the kids on a losing team, you learn to expect rewards regardless of how good you are at what you do. You learn not to work harder (it’s still fun when you aren’t good at something but you get a trophy for it anyway). You believe you must enjoy everything you do, including all the things you have to do between high school and meeting goals like getting your dream job. And then you become an adult who doesn’t want to do anything.

The western assumption of fragility over strength is probably what causes western kids to be so fragile. In fact, in the human growth and development class I took a year ago, I learned that if you shield infants and kids from stressful experiences, the part of the brain that buffers stress won’t fully develop and the kid won’t have the ability to cope with stress for the rest of his or her life.

But is causing stress in the life of your kid the right way to prevent that? I have a hunch that it isn’t.

I also have a hunch that there are plenty of Yale Law professors who didn’t grow up with “Chinese mothers.”

To read Chua’s story in full, click here. (And thanks to Alex for bringing it to my attention!)