Lent is here.

Forty days of death to self.

Of discipline.

Of more You, less me.

Of empty, quiet stillness.

Forty days in the desert.

Writer | Editor | Speaker

Lent is here.

Forty days of death to self.

Of discipline.

Of more You, less me.

Of empty, quiet stillness.

Forty days in the desert.

Click here to read my latest column, online now and in print in the Perspective section of tomorrow’s Tampa Bay Times.

It’s about my belief that even as part of a culture that loves social media and smartphones, another way of life is possible.

Until I was 10, I thought everybody was either Catholic (like my mom’s side of the family) or Jewish (like my dad’s). My horizons widened when, in fifth grade, my parents pulled me out of public school and put me in the private, non-denominational Protestant school where I studied through my senior year of high school.

Until I was 10, I thought everybody was either Catholic (like my mom’s side of the family) or Jewish (like my dad’s). My horizons widened when, in fifth grade, my parents pulled me out of public school and put me in the private, non-denominational Protestant school where I studied through my senior year of high school.

Every time a teacher discovered my Catholicism, what followed was one of three things: 1.) acceptance of me as a fellow Christian, 2.) fascination with and/or fear of the mystery that is my church or 3.) an unending aggressive attempt to persuade me to become Protestant. And the third response, to the chagrin of the teachers who tried it, ultimately achieved the exact opposite of its intended purpose.

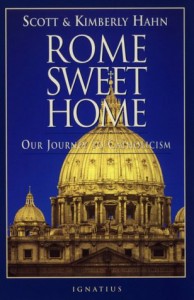

At school, somebody would protest something Catholic and at home, I’d study up. I’d read from the Bible and from books in my mom’s collection. I’d listen to cassette tapes of talks about the Church given by people like a professor named Scott Hahn. And the more I studied and read and listened, the more grateful I was for getting to grow up Catholic. So when recently, I stumbled upon the book Rome Sweet Home: Our Journey to Catholicism by Scott Hahn and his wife Kimberly, I got warm and fuzzy feelings as well as the urge to read it. As of tonight, it is the fourth book I’ve read start to finish in 2012.

I am not as into apologetics now as I was when I was a Catholic in a Protestant school (though I do explain, defend and question when necessary). But the book brought back memories of the years in which I was a little Catholic apologist and brought up points about why the Catholic Church teaches what it does that I hadn’t thought of in years. And their story — how the Hahns met and how they loved and the twists and turns their lives took later — is pretty riveting. For most of his life, Scott was the kind of Protestant who so disliked the Catholic church he’d call it the whore of Babylon. He was a Presbyterian pastor, a Calvinist and on a mission to persuade all the Catholics he met to become Protestant. Kimberly, the daughter of a Presbyterian pastor, wasn’t as anti-Catholic as her husband. But she never would have dated a Catholic, let alone married a Catholic. Which is why she was horrified when her husband became one. And she surprised everyone, when a few years later, she followed suit. Scroll down for some interesting points I dog-eared and/or underlined:

On studying what the Catholic Church teaches about contraception:

“Did our use of birth control reflect how God saw children or how the world saw children? … Perhaps it was more of an American attitude than a godly one to think of our fertility as something for us to control as we deemed best.” -Kimberly, page 36

On sola fide:

“We gradually became convinced that Martin Luther let his theological convictions contradict the very Scripture that he supposedly chose to obey rather than the Catholic Church. He declared that a person is not justified by faith working in love, but rather he is justified by faith alone. He even went so far as to add the word ‘alone’ after the word ‘justified’ in his German translation of Romans 3:28 and called Saint James ‘an epistle of straw’ because James 2:24 specifically states ‘…for we are not justified by faith alone.'” -Kimberly, page 41.

On sola scriptura:

“In my church history class, one of my better students … said, ‘Professor Hahn, you’ve shown us that sola fide isn’t scriptural—how the battle cry of the Reformation is off-base when it comes to interpreting Paul. As you know, the other battle cry of the Reformation was sola scriptura: the Bible alone is our authority, rather than the Pope, Church councils or tradition. Professor, where does the Bible teach that ‘Scripture alone’ is our sole authority?’

I looked at him and broke into a cold sweat.

I had never heard that question before. In seminary, I had a reputation for being a sort of socratic gadfly, always asking the toughest questions, but this one had never occurred to me.

I said what any professor caught unprepared would say, ‘What a dumb question!’ As soon as the words left my mouth, I stopped dead in my tracks, because I’d sworn that, as a teacher, I would never say those words.

But the student was not intimidated—he knew it wasn’t a dumb question. He looked me right in the eyes and said, ‘Just give me a dumb answer.'” Scott, pages 51-52 (Hahn stumped several of his Protestant preacher and professor friends with the same question. None were able to answer it.)

On a day Scott spent with Dr. John Gerstner, a “Harvard-trained, Calvinist theologian with strong anti-Catholic convictions” — a meeting the Hahns hoped would convince Scott to stay Protestant:

“‘Dr. Gerstner, I think the primary issue is what the Scripture teaches about the Word of God, for nowhere does it reduce God’s Word down to Scripture alone. Instead, the Bible tells us in many places that God’s authoritative Word is to be found in the Church, her tradition (2 Th. 2:15, 3:6) as well as her preaching and teaching (1 Pet. 1:25, 2 Pet. 1:20-21, Mt. 18:17). That’s why I think the Bible supports the Catholic principle of sola verbum Dei, the Word of God alone, rather than the Protestant slogan, sola scriptura, Scripture alone.’

Dr. Gerstner responded by asserting—over and over again—that Catholic tradition, the popes and ecumenical councils all taught contrary to scripture.

‘Contrary to whose interpretation of Scripture?’ I asked. ‘Besides, church historians all agree that we got the New Testament from the Council of Hippo in 393 and the Council of Carthage in 397, both of which sent off their judgments to Rome for the Pope’s approval. From 30 to 393 is a long time to be without a New Testament, isn’t it? Besides, there were many other books that people back then thought might be inspired, such as the Epistle of Barnabus, the Shepherd of Hermas and the Acts of Paul. There were also several New Testament books, such Second Peter, Jude and Revelation, that some thought should be excluded. So whose decision was trustworthy and final, if the Church doesn’t teach with infallible authority?’

Dr. Gerstner calmly replied, ‘Popes, bishops and councils can and do make mistakes. Scott, how is it that you can think God renders Peter [the first pope] infallible?’

I paused for a moment. ‘Well, Dr. Gerstner, Protestants and Catholics agree that God most certainly rendered Peter infallible on at least a couple of occasions, when he wrote First and Second Peter, for instance. So if God could render him infallible when teaching authoritatively in print, why couldn’t he prevent him from errors when teaching authoritatively in person? … how can we be sure about the 27 books of the New Testament themselves being the infallible word of God, since fallible Church councils and Popes are the ones who made up the list?’

I will never forget his response.

‘Scott, that simply means that all we can have is a fallible collection of infallible documents.’

I asked, ‘Is that really the best that historic Protestant Christianity can do?’

‘Yes, Scott, all we can do is make probable judgments from historical evidence. We have no infallible authority but Scripture. … Like I said, Scott, all we have is a fallible collection of infallible documents.’

Once again, I felt very unsatisfied with his answers, though I knew he was representing the Protestant position faithfully. I sat there pondering what he had said about this, the ultimate issue of authority, and the logical inconsistency of the Protestant position.

All I said in response was, ‘Then it occurs to me, Dr. Gerstner, that when it comes right down to it, it must be the Bible and the Church—both or neither.'” -pages 74-76

On yielding to God:

“My dad could sense the sadness in my voice.

He asked, ‘Kimberly, do you pray the prayer I pray every day? Do you say, Lord, I’ll go wherever you want me to go, do whatever you want me to do, say whatever you want me to say and give away whatever you want me to give away?’

‘No, dad, I don’t pray that prayer these days.’ He had no idea of the agony I was enduring over Scott’s being Catholic.

He said, genuinely shocked, ‘You don’t?!’

‘Dad, I’m afraid to. I’m afraid if I prayed that prayer, that could mean joining the Roman Catholic Church. And I will never become a Roman Catholic!’

‘Kimberly, I don’t believe it will mean you will become a Roman Catholic. What it means is that Jesus Christ is either Lord of your entire life, or he isn’t Lord at all. You don’t tell God where you will and won’t go. What you tell him is you’re yielded to him.'” -page 115-116.

For more information about the book, click here. For all the posts about books I read in 2012, click here.

“Because we are offered so many things that are immediately satisfying (albeit in a superficial way), it is hard to remain spiritually hungry. We give answers too quickly, take away pain too easily, and too commonly stimulate ourselves with nonsense. In terms of soul work, we dare not get rid of pain before we have learned what it has to teach us. Much that we call entertainment, vacations, or recreation are merely diversionary tactics, and they do not ‘re-create’ us at all. The word vacation is from the same root as vacuum, and means to ’empty out,’ not to fill up. One wonders how many people actually have such vacations!

We must be taught HOW to stay with the pain of life, without answers, without conclusions, and some days without meaning. That is the path, the perilous dark path of true prayer. It is how contemplative prayer differs from the mere recitation of prayers (which can actually be another diversionary tactic instead of any kind of self-emptying).” -Richard Rohr

As I kid, I had two primary chores (among many miscellaneous others):

folding laundry and emptying/loading the dishwasher.

Most days, I had two primary goals:

to not fold laundry and to not empty or load the dishwasher.

With three words at a time, I’d put off my chores:

“In a minute!”

“One second, please!”

“I’m busy now!”

My dad often had three of his own words for me:

“Always be working.”

Oh how I disagreed. How I knew the work would never end and that to acquiesce to a suggestion like “always be working” meant… I always would be working. How I did not imagine that in 2012, at 26, as a writer and a grad student, I’d discover that finally, I agree with my dad.

I know now that he didn’t mean “never take a break.” He meant “do what you need to do first and do what you want to do later.”

Because if you do what you want to do first, you’ll run out of time to do what you have to do. Then you’ll have to rush and it’ll be reckless and you’l be stressed.

Because if you do what you want to do first, you might not enjoy it as much. You’ll be preoccupied by knowing there’s stuff you’ve got to do later (especially if it’s stuff you don’t want to do).

Because it feels really good when at the end of the day — as a result of doing what I have to do first — I have time left to work out, read for leisure and write on my blog.

This is not to say it isn’t still a challenge.

Most afternoons, when I get home from work, I say, “In a minute!” to myself when I want to watch back to back episodes of the Waltons instead of making flashcards.

Gratefully, most afternoons, I shut off the TV and think of the following:

“Always be working.”